BLOG: Building Communities through Biophilic Design

Sadiqa Jabbar from our London office attended a Biophilic conference at the beginning of the month, check out her blog below on ‘Building Communities through Biophilic Design’.

On 4-5th September 2018, I attended the two-day Activating Biophilic Cities conference hosted by the University of Greenwich. It was an extremely insightful and valuable event, which if anything reminded me of how much nature is intrinsic to our everyday lives, and must be well considered into how we design the built environment. And no, valuing the importance of biophilia does not mean one has to be an ‘eco-warrior’ nor a sustainability guru!

The conference had a good set of speakers, covering a wide range of biophilic topics and schemes at various scales in size and budget. It was great to start with overarching themes and introductions to the topic before delving into the nitty-gritty workshop discussions. The mix of professionals amongst the attendees ranged from artists, architects, interior and landscape designers, to biophilic consultants, academics, students, planners, and energy consultants. The hosts mentioned the value of inviting decision makers for an even richer and more holistic dialogue next time. To really make a difference community groups, developers, contractors, financers, and even the die-hard sceptics need to be part of the discussions to bring biophilic design into the mainstream norm.

The range of case studies and research undertaken was fascinating with many projects that inspire the imagination worthy of further exploration. Showcasing the successful biophilic projects strengthened the case for nature inspiring good design. We always need that little seed of inspiration to reinvigorate and kick start our creative juices.

The conference enabled me to reminisce the various design projects throughout my architectural education, all of which incorporated biophilia in some shape or form as a default paradigm, albeit using different terminology. Whether through courtyard gardens, allotments, birds’ sanctuary, floating pools, gardens, playgrounds, and greenhouses, or considering natural daylight and ventilation, site orientation, climate, infrastructural links, topography, accessibility, demographics and local amenities, biophilia was always part of the design process.

In architectural practice, all of these factors still do apply. However even though the Building Regulations, BREEAM, and various Planning policies and sector specific design guidelines provide a framework for the incorporation of biophilia in some form, what happens during the design process (without a well informed client or design team to encourage and challenge for creative implementation ideas) is that components such as landscaping, acoustics, and MEP services (essential to the physical, psychological, and social health and wellbeing of the space users) are often value engineered as luxurious ‘nice haves’.

Biophilia is an important factor to consider within the design of buildings, spaces, and places. It is an integral part of the design process, and should be included in discussions with clients, consultants, and contractors during all stages of the project. It can be incorporated at various scales and does not necessarily need to cost an arm and leg, nor does it have to be specifically high or low tech, that’s the beauty of it. The real challenge for designers working for clients and contractors not sold by biophilic design, is to incorporate the concepts into the design in a creative way that is so intrinsic to the scheme that its value is genuinely appreciated and understood. To do so in a cost effective way is invaluable.

Biophilic design is conducive to the way we live, work, learn, play, worship, and recuperate, both individually and as communities. It is not just about plants and landscaping, and one does not have to be a die-hard sustainability enthusiast to promote the benefits. If carefully considered we can create spaces that calm, relax, inspire, energise and rehabilitate. At its most simple it’s about bringing in natural light and ventilation, or providing views of the outside world to an internal environment, while playing with materials, textures and colours. At its most complex it may combine a series of different species of plants, trees, water, ecosystems, and wildlife into the design. At its best, biophilic design considers all, or as many of, the fives senses. Ultimately we must create a balance between natural and man-made elements to enhance the mental, physical, and social health and wellbeing of our fellow human beings.

Photo showing one of University of Greenwich School of Architecture’s rooftop terraces.

Everyone’s experience and perception of nature is different, there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution. While it would be near impossible to please everyone, and all at the same time, we should take into consideration that we live in societies where people belong to various communities, each bringing unique qualities, and experiences from a variety of different cultures and belief systems. In an ever globalised and urbanising world, we need to be appreciative of our differences and not assume that everyone thinks, feels, or acts the same as us. This should follow through in the design of the biophilic spaces we create.

What is it?

To contextualise the discussion, biophilia is a term first used by German psychologist Erich Fromm in 1964 referring to human beings’ “love of life or other living organisms”; E O Wilson was the first to publish a book on the topic in 1984. In his 1993 book, Wilson defines Biophilia as “the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms. Innate means hereditary and hence part of ultimate human nature.” The merriam-webster.com definition refers to biophilia as “a hypothetical human tendency to interact or be closely associated with other forms of life in nature”.

Therefore biophilic design is the incorporation of natural elements into the design of objects and human inhabited buildings, spaces, and places. This may be through natural daylight and ventilation, views out from internal spaces, site orientation and contextual relationships, the use and positioning of plants, trees, water features, fragrances, to the use of material colours and textures. Ultimately it is not just about incorporating plants and flowers; biophilia is so much more.

If you would like to read more about biophilic design, www.biophilic-design.com provides a great introduction and overview by Dr Stephen Kellert and Elizabeth Calabrese with a downloadable book to read offline at your leisure. Oliver Heath Design have a comprehensive explanation of the concept on their website.

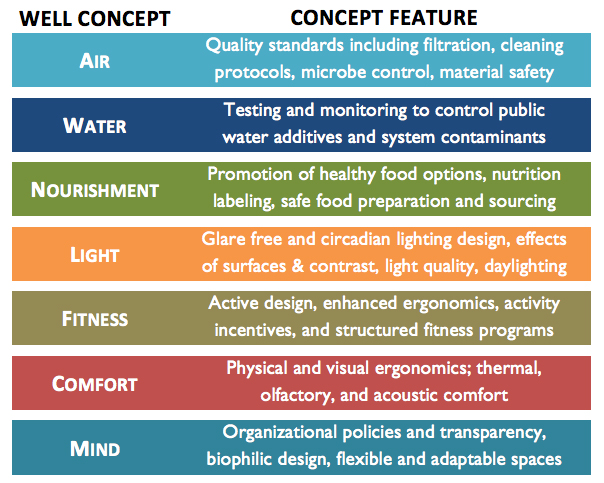

The WELL Building Standard, which I discovered a few weeks ago, was discussed by a number of the conference speakers. The Standard provides a set of guidelines to help promote the concept of biophilia through the wellbeing of buildings. Delos™ researched and scientifically developed each of the over 100 standards based on 7 key concepts for creating healthy buildings that enhance the wellbeing of its occupants. This means designing environments with due consideration of air quality, water, light, people’s nourishment, fitness, comfort levels, and the subsequent impact on their minds using innovative methods.

WELL Building Standard Concepts. Source: Crew Network.

Benefits

There are numerous benefits of incorporating biophilia into the spatial design. Considering the rise of deaths and chronic illnesses caused by toxic fuel inhalation it is imperative that we use plants and trees to improve air quality by increasing oxygen levels and reducing the impact of toxic fumes. Internal spaces can be managed by the use of aromatic fragrances (depending on plant and material selection) catering to our sense of smell. Plants and trees can help reduce levels of toxic fumes in streets, making them more people friendly, attractive, and inviting spaces.

Being able to see or experience nature creates a sense of calmness and is known to help lower stress levels at work. Thus aiding the reduction of stress related illnesses and staff absenteeism, leading to increased levels of productivity and staff retention, and potentially improving business leads and profit margins. For families reduced stress levels could improve their quality of life by creating better environments for building and maintaining familial relations, friendships, and communities.

Procrastination is known to be good for reflecting and enhancing creative thinking. Providing natural views to float away in thought can provide people the opportunity to take a moment to reflect and come back refreshed to continue a task at hand. A TED Talk that I recently viewed by Manoush Zomorodi, ‘How boredom can lead to your most brilliant ideas’ is worth a watch.

Spaces with elements of nature, real or mimicked, can help create inspiring learning spaces that also provide a sense of security. Whether designing nurseries, schools, or universities for children, adolescents, or adults, everyone has a different rate of learning. Providing that connection with nature can enable a softer and more intuitive way to explore, develop and collaborate…or retreat from the world! As designers we should create spaces that facilitate an organic occupation that feels right for the user(s). This video, ‘Interface + Open City Biophilic Tour of London‘ is pretty powerful in conveying the importance of biophilia in learning environments.

Studies have shown that the inclusion of biophilic design in healthcare facilities improves the rate of patient rehabilitation. Listening to the needs and aspirations of the occupants can help designers provide them with dignity and the kind of care that they need in their moment of vulnerability. The connection with nature and outlook from internal spaces create a sense of calmness, hope, and ease. Spaces where one can escape from the reality of the trauma, places that evoke a sense of value, trust and belonging to a community.

Maggie’s Centre, Charing Cross Hospital.

Nature can work wonders to bring people together. Biophilic design can bring a positive difference to communities by encouraging interaction in a more organic way. Places where people can accidentally bump into each other, have impromptu conversations, and find common ground is a beautiful concept. In an ever increasingly paranoid and suspicious world, finding places where we can relax, feel secure, and enjoy (whether individually or as a group) are a necessity.

Barriers

There may be other barriers but after the workshop discussions, it seemed to me that the following were the top challenges for progressing biophilic design into everyday practice.

Cost is the primary barrier mainly due to the misconception that bringing nature into building and spatial design will be an expensive endeavour. Depending on the scale and scope of biophilia, it need not be so pricey. For example the brief could simply be to design a space to bring in natural light and ventilation, and create external views. Or it could mean incorporating materials such as timber or soft fabrics, or visually bring in nature through the choice of colours, images, patterns, and textures.

Not everyone loves nature whether through fear (of animals, insects, and spatial constraints), allergies, or cultural differences in attitude or approach. Dr Bridget Snaith and Anna Peters undertook research exploring the cultural perspectives of nature’s connection with health and wellbeing. They discovered some communities have negative perceptions of nature, considering it dirty or unhygienic, concerns over free roaming animals i.e. dogs, child safety, and levels of interaction. They also found that some scents were not as appealing as one might think, for example they discovered that lavender was considered sickly by hospital patients. Therefore nature is not just an all encompassing whole, everyone has their own perception of what it means to them. Therefore when considering biophilic design, one must consider the unique settings and human qualities that come with it.

There are sceptics to the ‘biophilic movement’ for whom evidence is required with proven track records of buildings, spaces, and places where biophilia has shown its viability as a cost effective option. This often leads to the lack of will to drive through the existing legislation (Planning policies, BRE, BREEAM, and Passivhaus Standards) into practice. The only way to do so is to do the research, and become knowledgeable and creative in the way biophilia is incorporated into the design. Designers need to own the process whilst including their clients in the development of biophilic design organically in their schemes.

The lack of understanding of what biophilic design is, the benefits, and motivation to find cost effective solutions for each unique project is an obstacle. To address this an education in biophilia at various levels and across sectors would help bring the value of connecting with nature to a wider range of people.

Another barrier highlighted was the friction between various stakeholders involved in the design and decision making process, which leads to a lack of collaborative thinking. Finding a balance between the needs, aspirations and realities of each stakeholder can help create a holistic dialogue that could help bring biophilia to a wider community.

Good practice

Case studies discussed ranged from global biophilic cities such as Wellington (Nature Map programme), Singapore (city within a garden), Birmingham (currently UK’s only biophilic city), and Edmonton (Ecological Network), urban developments such as the Elephant Park in South London and the Canary Wharf Corporate Diversity Strategy, to smaller interior design schemes such as office refurbishments, treatment of learning and healing spaces, and biophilic print design.

The Hockerton Housing Project in Nottinghamshire is a community that lives, works, plays, and blends in with its surroundings in as organic way as possible. Rainwater is harvested, the community grows most of their food, they recycle their waste materials, and the houses generate clean energy. The development is run as a non-profit cooperative that undertakes tours, workshops, courses, and consultancy services to cover their operation costs.

Maggie’s Centre buildings are a wonderful series of architecture that incorporate biophilic design in such a wonderful space that even if you are not a patient, you feel immediately relaxed and cared for. I had the opportunity to visit the Rogers’ Charing Cross building a few years ago during an Open House weekend and have been mesmerized and inspired by it ever since. The combination of colours, natural light, and views into winter gardens from each room is sensitively considered for the building users. It felt like an oasis amidst the heavy traffic immediately outside the site compound. I wrote about it in my first blog ‘Buildings Spaces Places‘ in 2011.

Hockerton Housing Project in Nottinghamshire.

One of the many education buildings designed by my colleagues here at MEB Design Ltd screams biophilia to me. Beaudesert Performing Arts School in Gloucestershire combines natural materials, shapes, and form to produce a building that sits well within its natural context. The amount of natural light that streams through into the building with framed views out to the surrounding external landscape is just incredible.

The use of graphics to mimic biophilia is another subtle way of bringing nature indoors. Many product manufacturers have access to advanced technology enabling them to find creative ways to mimic nature through graphic design. Whether through digital printing or surface finishes the connection to nature can be visually engineered through the selection of wallpaper, carpet, furniture, and fabric design. For example floral patterns and designs are very popular in the textile industry.

If patterns aren’t your ‘thing’, then you can try a palette of textures and natural materials such as stone, timber, glass, and earthenware combined with natural hues and tones to create a biophilic interior. Australia’s Urban Rhythm created a comprehensive blog that is a great way to begin thinking about colour choices. Smartstyle Interiors’ blog on biophilic interiors is also worth a quick read.

Example of subtle use of colour, texture and patterns to bring nature into an interior. Source: El Mueble.

Thank you for reading this blog! With the hope it hasn’t put you off, go do more research into biophilia, and let us know your thoughts on this topic.

Useful References

Browning, W., Ryan, C., and Clancy, J. 2014. The 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design – Improving Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. Terrapin Bright Green.

Cooper, C., and Browning, W. 2015. HUMAN SPACES: The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workplace. Interface DesignLab.

Heath, O., Jackson, V., and Goode, E. 2018. Creating Positive Spaces – WELL Building Standard™. Interface DesignLab.

Heath, O., Jackson, V., and Goode, E. 2018. Creating Positive Spaces Using Biophilic Design. Interface DesignLab.

Heerwagen J., and Hase, B. 2001. Building Biophilia: Connecting People to Nature in Building Design.

Interface. 2016. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design.

Kellert, S., and Calabrese, E. 2015. The Practice of Biophilic Design. www.biophilic-design.com